Authors: Elizabeth AKPAN, Melissah WEYA & Oluchi AUDU

The use of AI in everyday life is increasing rapidly across areas such as education, finance, and health. In healthcare, especially, people are increasingly turning to AI for support with child care, self-care, and other health-related decision-making. Yet, despite this uptake, there’s still very little research on how the use of AI for health information actually performs when real people use it in real-life contexts.

At the YUX Cultural AI Lab, much of our AI work has focused on exploring human-centred design and UX research methods to evaluate AI systems (both at the model and at the product/user levels), going beyond the traditional focus on safety and accuracy that dominates most AI evaluations today. Instead, we emphasise how these systems resonate with users, particularly from cultural and contextual perspectives. To do this, the YUX team conducted human-centred research using methods such as “Cultural Teaming” (adapted from Chiu et al., 2024) alongside large-scale quant-qual surveys run as diary studies. These approaches allowed us to assess AI systems in health use cases not only in terms of model performance, but also cultural relevance, clarity, trust, and the overall experience of using these tools in realistic, everyday situations.

Cultural Teaming

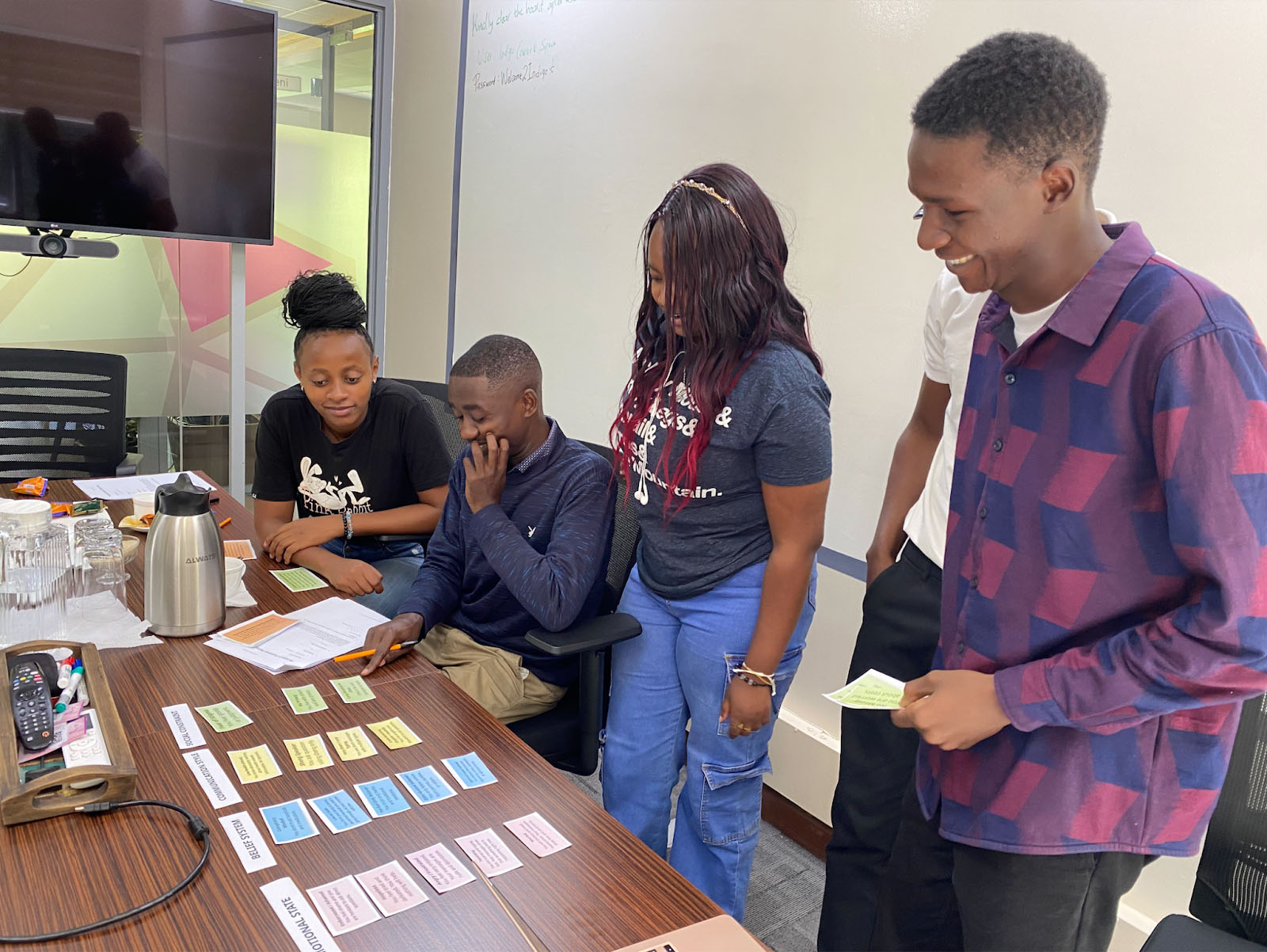

The in-person “Cultural Teaming” sessions in Kenya combined scenario-based testing, individual reflection, and creative role play exercises to examine how ChatGPT responds to real-world, health-related situations as experienced by Kenyan users. Participants interacted directly with the system using locally grounded prompts, then rated its responses to surface cultural, linguistic, and contextual gaps. We conducted two sessions in total, each with four participants who regularly use ChatGPT for health-related information.

Each session was structured around three main activities:

1. Participant Led Exploration where participants were given the opportunity to freely explore the chatbot and ask health-related questions as they would in real-life situations. The goal of this activity was to establish a baseline understanding of how participants naturally interacted with the chatbot and to observe the types of health questions they typically posed.

2. Real-life Scenario Testing, where participants were assigned pre-defined scenarios designed to reflect realistic health situations. These scenarios simulated a range of health-related questions, with a focus on symptom triage, chronic care pathways, and maternal and neonatal care. After each interaction, participants were asked to evaluate the chatbot based on criteria such as cultural relevance, clarity, and trustworthiness.

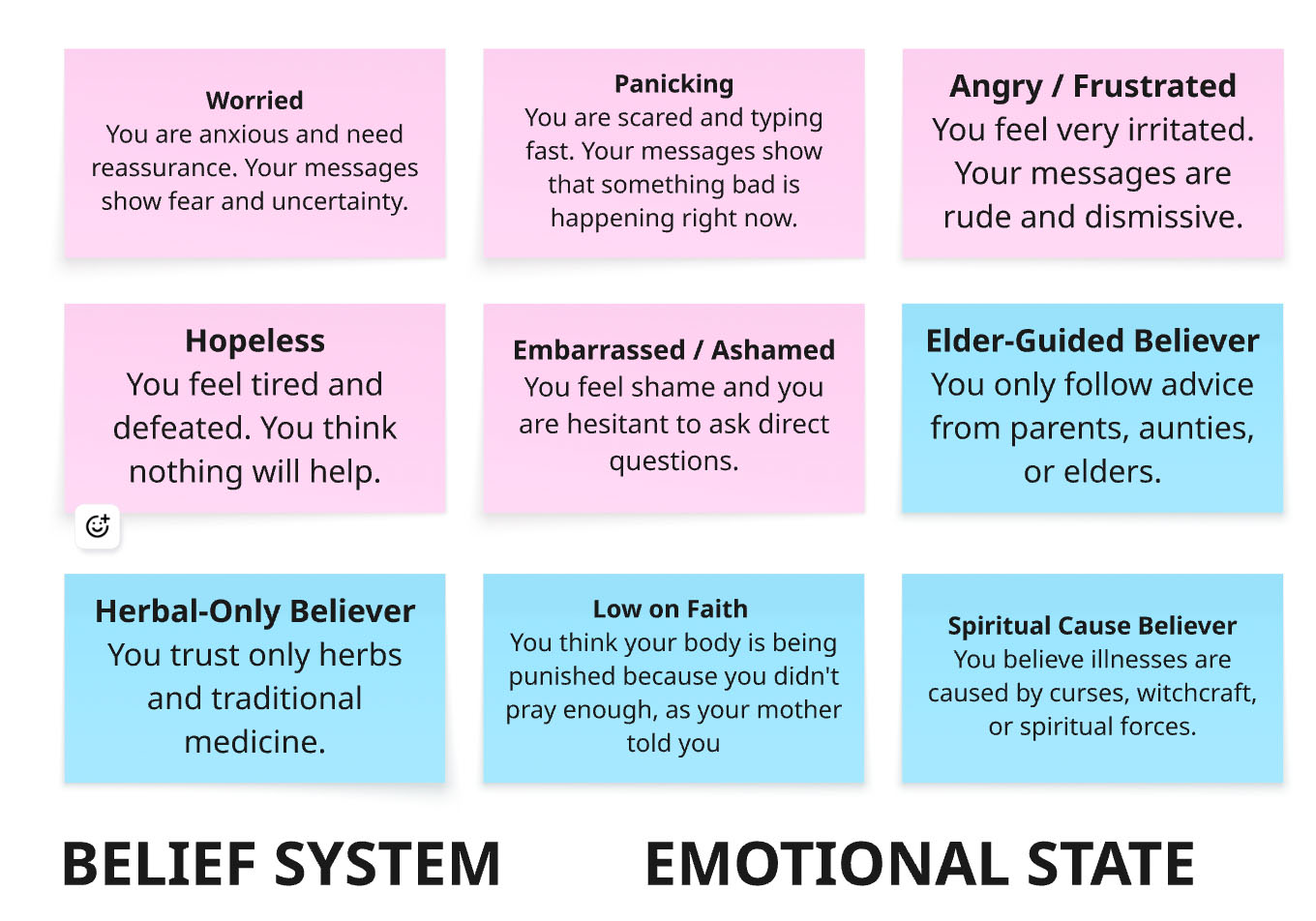

3. Adversarial Testing, where participants worked in pairs and were assigned persona cards to simulate complex, real-world health scenarios with multiple influencing factors. The persona cards represented dimensions such as social constraints (e.g., limited financial resources, long distance to a clinic), communication style (e.g., Sheng speaker, code-switching), emotional state (e.g., panicked, embarrassed, or ashamed), and belief systems (e.g., reliance on herbal medicine, belief in spiritual causes of illness). Participants were asked to assume the roles described in their persona cards and use them to generate prompts for the chatbot. Following the exercise, they rated the chatbot’s responses using the same evaluation criteria outlined above.

Some of the key learnings from using this methodology include:

Scenarios brought out creativity and context: When engaging with scenarios, participants naturally brought in real-world context, personal experience, and local knowledge. Some participants were keen on evaluating the response based on what they knew to be available or appropriate in Kenya, such as specific prescription recommendations and local healthcare realities. At first, we pre-assigned categories of scenarios for participants to choose from in the morning session. In the afternoon sessions, however, we allowed participants to select scenarios they resonated with, and we saw rich context emerge that also challenged our assumptions. One male participant selected a maternal health scenario involving an infant with constipation, drawing from a situation he personally navigated. From our group discussions, we observed that this enabled him to be more thoughtful and probing with his prompts and more critical in questioning the AI’s responses, resulting in richer feedback.

Scenarios created safety: Using scenarios allowed participants to “step into” a situation without needing to expose their own personal histories directly. Participants were more comfortable testing, questioning, sharing and even challenging responses when interacting through a scenario rather than speaking only from personal experience.

Develop scenarios into lightweight personas: We saw clear value in taking the scenarios further by developing them into lightweight personas with basic demographic and contextual details, e.g., age, education, family context, and background. This would allow participants to take up the scenario and engage more deeply with the tools being tested. During the discussions, it appeared that the participants would be more willing to explore edge case scenarios when they could attribute actions and decisions to a defined “person” rather than themselves.

Grouping participants enables richer prompt generation: During the adversarial testing round, we found that pairing participants added significant value, particularly when using the scenario cards. Working in pairs encouraged discussion, diverse perspectives, and collaborative thinking, which led to more nuanced and realistic prompts for the chatbot.

While these learnings showed us where this method could go next, they also surfaced concerns we had going into the sessions and helped us frame considerations and recommendations for future sessions. One of the concerns we had going in was the risk of dominant voices. As with many group discussions, a few people can end up shaping most of the conversation. Without careful facilitation, quieter participants may contribute less, which limits the range of ideas shared. We recommend that facilitators have a clear plan for how they want the sessions to run and integrate activities such as icebreakers, breaks, and periodically reorganising groups in order to help balance participation. We also recommend incorporating moments for individual reflection, as we did, where participants are invited throughout the session to submit written reflections.

Diary-Based Surveys

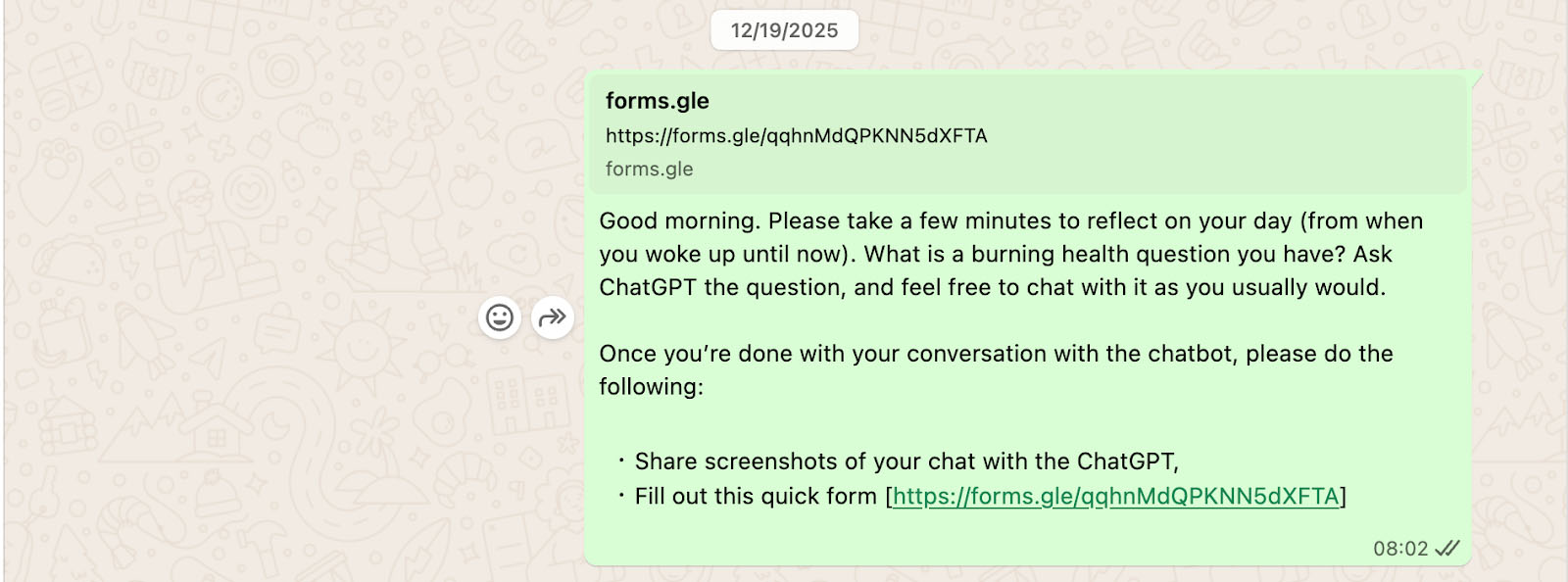

The large-scale, mixed-methods, diary-based survey was designed to capture a high-fidelity snapshot of how individuals integrate Large Language Models (LLMs) into their daily health management. By utilising a diary study format, the research aimed to move beyond theoretical sentiment and into the "lived experience" of the participants. The participants were pinged twice daily on WhatsApp with an open-ended question: “what is a burning health question you have? Ask the chatbot the question, and feel free to chat with it as you usually would.” The survey questions that followed, along with the main question, were designed to uncover the specific nature of unprompted health queries, the resonance of AI-generated advice, and the friction points at which guidance fails or leads to misunderstandings.

What did we learn after 5 days of running these survey diaries with 10 participants across two countries — Kenya and Nigeria? Well, the learning began during recruitment.

During screening calls, a notable discovery emerged: several participants were using Grok as a standalone application rather than through the integrated X (formerly Twitter) interface. Furthermore, early interactions revealed a distinct user preference for assertive communication styles; participants preferred chatbots that provided direct, confident answers rather than those that mirrored user queries or adopted a neutral, inquisitive stance. To honour these naturalistic behaviours, the study allowed participants to use the interface with which they were most comfortable. This resulted in a split where two participants from Nigeria utilised Grok, while the remaining eight opted for ChatGPT, ensuring that the data reflected genuine, habitual interactions rather than forced engagement with an unfamiliar tool.

This diary study approach builds on a methodological framework we used in a previous study to analyse the digital curiosity and behaviours of African users at scale. By leveraging real-time, longitudinal data collection, we aimed to move beyond the constraints of typical usability testing. This study sought to replicate the success of prior large-scale surveys by capturing the nuances of health-seeking behaviour in practice. By meeting users where they are—primarily via WhatsApp—the study sought to bridge the gap between technical AI performance and the messy, urgent realities of daily health management in diverse cultural contexts.

Despite the richness of the data collected, the post-study analysis highlighted several critical areas for methodological refinement. A primary concern was the effect the incentive had on the participants. As the study progressed, the authenticity of some health queries appeared to diminish as participants prioritised completion for compensation. To mitigate this in the future, we recommend varying the study length or integrating scenario-based prompts—similar to those used in cultural teaming focus groups—to maintain high-quality engagement. Furthermore, we identified a need for deeper participant profiling. Future recruitment should look beyond whether a participant searches for health info online and instead probe how they conduct those searches during the onboarding call.

Finally, the study underscored the need for adaptive frequency among participants experiencing active health crises. One participant, who was ill during the study, had difficulty maintaining the twice-daily survey completion schedule. For studies specifically targeting health contexts, including a low-frequency option for those currently unwell would ensure the methodology remains inclusive and does not inadvertently exclude the very perspectives most relevant to the research.

Conclusion

This study is a first step in testing and comparing different evaluation methods. We found that diary studies work well for testing at scale, while cultural teaming exercises are better for creativity and deeper insights.

One key learning from exploring these two methodologies is that scaling them becomes much easier with a proper platform that integrates annotation and evaluation tools. This allows for more structured data collection, easier analysis, and consistent tracking of insights across participants. The YUX Cultural AI Lab is currently developing a platform with these capabilities, so stay tuned!

In the meantime, follow the Masakhane community of practice on responsible AI design and evaluation, where we continue to explore and discuss innovative methods for AI evaluation.