Across East Africa, teachers are quietly reshaping education with low-cost, context-specific innovations, from feedback boxes that amplify student voices to tree nurseries that teach climate resilience. This case study explores what drives these innovators, and how Schools2030, with YUX as the East Africa learning partner, is supporting and learning from them to scale teacher-led change. By the end of this engagement, YUX produced a set of knowledge products to inform program and process-level improvements, including star teacher profiles, innovation case studies, and learning reports.

Schools2030: Teachers at the Forefront

Schools2030 is a global movement for holistic learning and teacher leadership, led by the Aga Khan Foundation that brings together a diverse coalition which includes educators, school leaders, civil society, researchers, international organisations and governments across ten countries and 1,000+ schools and community learning sites. Schools2030’s goal is to improve quality teaching and holistic learning, and to foster resilient education systems across the world, including for those living in remote regions and those facing multiple forms of marginalisation and crises. This is done through a focus on teacher agency – recognising educators as leaders, innovators and active agents in education reform.

Each year, teachers take part in a human-centered design journey to develop classroom-based innovations.

Through workshops and design coaching, they identify challenges, prototype solutions, and share what works.

YUX’s Role as the Learning Partner

In 2024, YUX Design joined as Schools2030’s East Africa Learning Partner to support implementation research across Kenya, Uganda, Mainland Tanzania, and Zanzibar. While previous learning partner efforts focused on identifying strengths, areas for improvement, and barriers in the Human-Centered Design process, last year, YUX — in collaboration with AKF East Africa — shifted the lens. Instead of diagnosing process gaps, our research explored the drivers of success: which teachers thrive as innovators, and what enables them to do so?

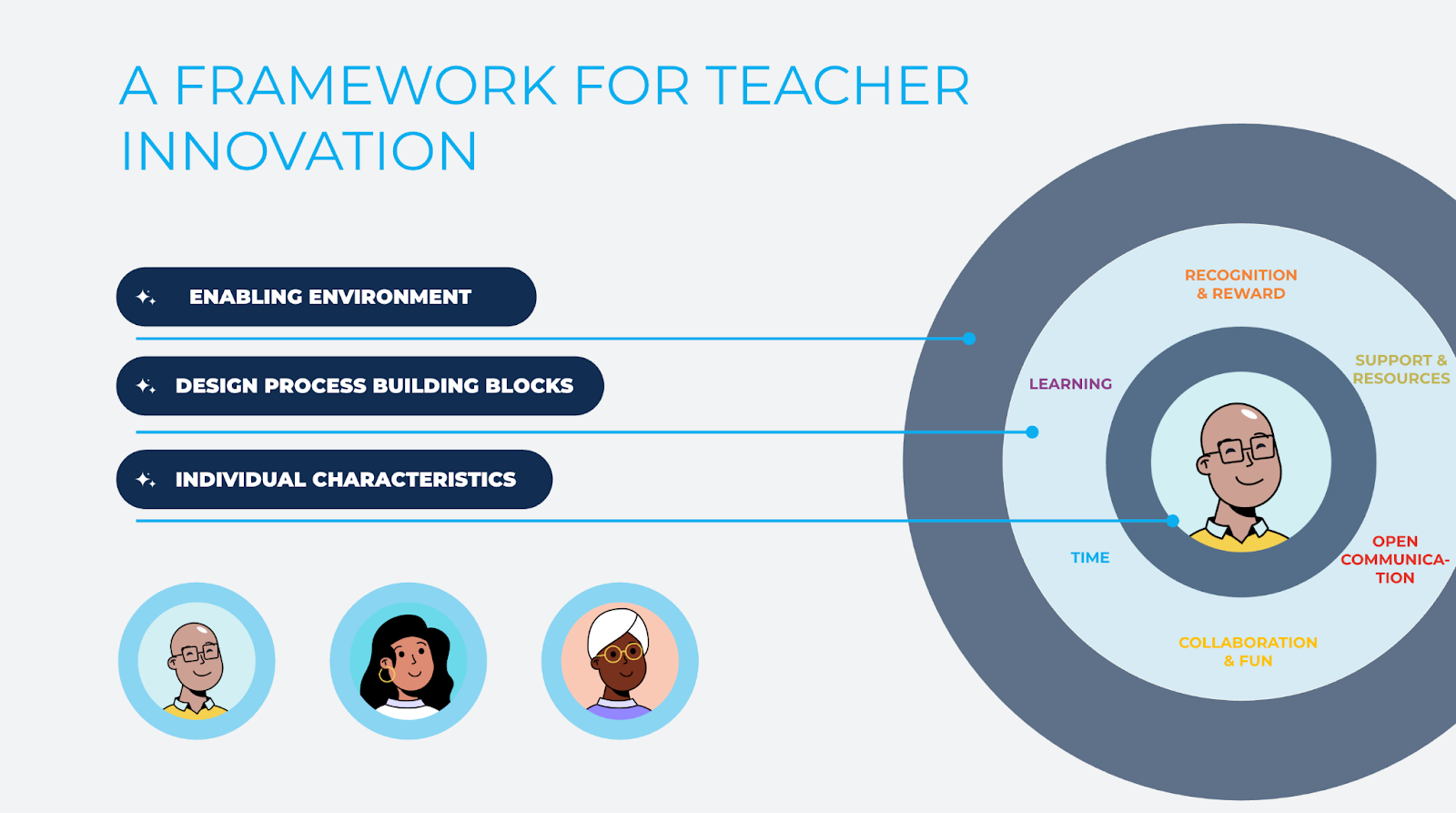

To structure this inquiry, we built on Schools2030 East Africa’s framework for teacher-driven innovation, built from previous year’s learnings on what constitutes an effective design process. This framework has three layers:

Internal teacher characteristics – traits that enable teachers to adopt and embrace innovative practices.

Design process building blocks – time, recognition, open communication, access to support, and opportunities for collaborative and fun learning.

The enabling environment – including resources, infrastructure, school culture, and social norms that enable innovation.

In essence, the framework reimagines design facilitation as a dynamic system where enabling conditions, institutional structures, and teacher agency converge to drive innovation in education. It serves as both:

- A Diagnostic Tool: Helping organizations like Schools2030 identify barriers to HCD adoption.

- A Strategic Guide: Providing targeted recommendations for strengthening the design process and improving teacher engagement.

Earlier years of research had focused mainly on the second layer: the design process itself. In 2024, we extended our attention to the inner layer (individual teacher characteristics) and the outer layer (enabling environment). This shift was rooted in a key realization: not all teachers necessarily want to, need to, or can become designers and innovators. To increase the likelihood of impactful innovations, we needed to identify early adopters of HCD and explore how best to support them.

A Positive Deviance Approach: Learning from Early Adopters to Develop Star Teacher Profiles

We therefore took a positive deviance approach, deliberately focusing on teachers who were engaging strongly with the innovation process and developing promising solutions. Through in-depth interviews and school visits, we traced their personal and professional journeys—examining motivations, values, and defining career moments. This helped us understand not only what they designed, but also why they chose to innovate in the first place. The purpose of the interviews was to gather data to create personas representing teachers who excel in the innovation program—referred to as star teachers.

To develop the personas, grouped recurring themes around teacher values, motivations, behaviours, and enabling conditions, and identified patterns that appeared across multiple interviewees. These patterns formed the basis for the ‘star teacher’ profiles.

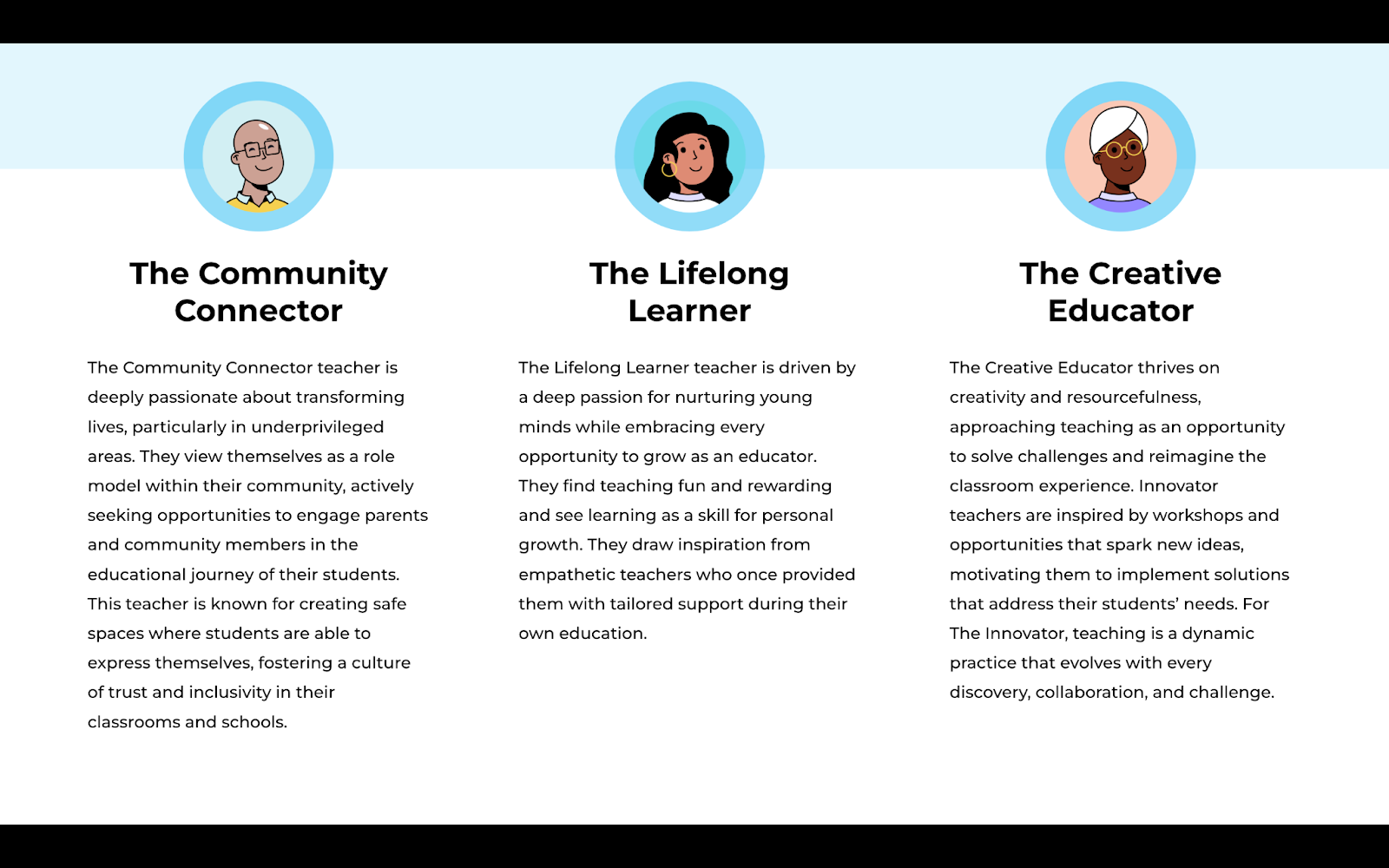

From this research, three recurring profiles emerged:

- The Community Connector – Passionate about transforming lives in underprivileged areas, mobilizing parents, and fostering inclusive classrooms.

- The Lifelong Learner – Curious and growth-oriented, always seeking new knowledge and refining practice.

- The Creative Educator – Resourceful problem-solvers who reimagine classroom experiences, inspire peers, and integrate innovative strategies.

These personas are not rigid categories; rather, they provide useful tools for guiding future program cycles. For example, they can help adapt teacher supports, refine selection criteria for new cohorts, or even serve as reflective tools for teachers to identify their strengths and growth areas. We recognize these personas are based on a small sample and should be refined with further research.

How teachers are driving change

Across East Africa, we found teachers developing creative, context-specific solutions through the Schools2030 design process. We noted the following innovative examples during our school visits:

- In Kenya, a pre-primary teacher used images from old school books to create 'talking magazines' that children used to improve their communication skills by talking about the images they notice in the magazines.

- In Mainland Tanzania, teachers engaged parents and community members in climate action projects such as tree nurseries and microforests, with families contributing seeds, manure, and even funds to support implementation.

- In Zanzibar, a pre-primary teacher leveraged his tree planting initiative to engage a student with a disability, building her confidence, social connections, and academic progress, while fostering greater inclusion among her peers.

- In Uganda, a secondary school teacher guided students to collect and visualize data from the school’s sick bay, enabling the administration to address recurring health issues like flu and typhoid.

- “Before the programme, I only thought of making teaching tools. I didn't think of gardening and tree planting, because most of time I have been working in preparing the teaching aid tools”

Understanding Enabling Environments

Additionally, our research highlighted the importance of supportive ecosystems for teacher-driven innovation. Teacher success was never just about individual drive. We learned about the importance of the following:

- School leadership support – Headteachers who provided approvals, resources, and encouragement made innovation possible.

- Peer collaboration – Teachers who shared devices, co-taught, or gave feedback fostered collective problem-solving.

- Dedicated design coaches – Localized, consistent mentorship proved invaluable in sustaining momentum.

- Community engagement – Parents and community members who contributed resources and ideas enhanced ownership and sustainability.

Our Outputs

By the end of this engagement, YUX produced a set of knowledge products to inform program and process-level improvements, including:

- Star teacher profiles - profiles illustrating the characteristics of teachers who thrive as innovators.

- Innovation Case Studies – practical examples of classroom innovations in action

- Learning Reports – country-specific and cross-cutting findings across Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and Zanzibar, along with strategic recommendations for process-level enhancements.

Looking Ahead

The next phase of Schools2030 is to incubate and scale high-potential innovations so they can spread beyond classrooms and shape education systems. By learning from early adopters—the ‘star teachers’ leading change—we can reimagine what’s possible when educators are trusted as designers of the future.

YUX’s work demonstrates that teacher-driven innovation thrives at the intersection of individual agency, supportive design processes, and enabling environments. By learning from early adopters—the “star teachers” who embrace innovation—we can better design strategies that identify, nurture, and sustain frontline innovators across East Africa.

The resulting personas offer practical ways to apply these insights: they can help guide the selection of teachers in future cohorts, form teams with complementary strengths, support teachers’ self-reflection on their own capabilities, and inform the design of tailored coaching and resources. With further refinement and validation across a larger and more diverse sample, this approach could be extended to additional regions and countries, strengthening Schools2030’s ability to systematically support teacher-led innovation at scale.

Acknowledgements

Project co-leads - Rajay Shah (Kenya), Clara Muthoni (Kenya), and Sasha Ofori (Ghana)

Researchers - Ocheck Msuva (Tanzania), Noel (Uganda), Patricia (Uganda) etc,